hreflang is a technical solution for sites that have similar content in multiple languages. A site owner wants search engines to point people to the most “fitting” language. Say a user is Dutch, the page that ranks is English, but there’s also a Dutch version. You would want Google to show the Dutch page in the search results for that user. This is the type of problem hreflang was designed to solve.

In this (very long) article we’ll discuss:

1.What is hreflang meant for?

hreflang is a method to mark up pages that are similar in meaning but aimed at different languages and/or regions. You can use this for three types of variations:

Content with regional variations like en-us and en-gb.

Content in different languages like en, de and fr.

A combination of different languages and regional variations.

You can use hreflang to target different markets that use the same language. This is a fairly common use case. Using hreflang you can differentiate between the US and the UK, or between Germany and Austria.

2. What’s the SEO benefit of hreflang?

So why are we even talking about hreflang? What is the SEO benefit? There are two main reasons, from an SEO point of view, why you should implement it.First and foremost, if you have a version of a page that you have optimized for the users language and location, you want them to land on that page. Having the right language and location dependent information improves their user experience and thus leads to fewer people bouncing back to the search results. Fewer people bouncing back to the search results leads to higher rankings.

The second reason is that hreflang prevents a duplicate content problem. You might have the same content in English on different URLs aimed at the UK, the US and Australia. The difference on these pages might be as small as a change in prices and currency. Google might not understand on its own what you’re trying to do and see it as duplicate content. With hreflang you make it very clear to the search engine that it’s (almost) the same content, just optimized for different people.

.

3. What is hreflang?

hreflang is code, which you can show to search engines in three different ways, more on that below. With this code you specify all the different URLs on your site(s) that have the same content. These URLs can have the same content in a different language, or the same language but targeted at a different region.

4. What does hreflang accomplish?

Who supports hreflang?

hreflang is supported by Google and Yandex. Bing doesn’t have an equivalent, but does support language meta tags.

In a complete hreflang implementation, every URL specifies which other variations are available. When a user searches, Google goes through the following process:

it determines that it wants to rank a URL;

it checks whether that URL has hreflang annotations;

it presents the searcher with the results with the most appropriate URL for that user.

The users current location and his language settings determine the most appropriate URL. A user can have multiple languages in his browser’s settings. I, for instance, have Dutch, English and German in there. The order in which these languages appear in my settings determines the most appropriate language.

5. Should you use hreflang?

Based on what we’ve learned on what hreflang is and how it works, we can determine if you should use it. You should use it if:

you have the same content in multiple languages;

you have content aimed at different geographic regions, but in the same language.

Whether the content you have resides on one domain or multiple domains does not matter. You can link variations within the same domain but can also link between domains.

Architectural implementation choices

One thing is very important when implementing hreflang: don’t be too specific! Let’s say you have three types of pages:

German

German, specifically aimed at Austria

German, specifically aimed at Switzerland

You could choose to implement them using three hreflang attributes like this:

de-de targeting German speakers in Germany

de-at targeting German speakers in Austria

de-ch targeting German speakers in Switzerland

However, which of these three results should Google show to someone searching in German in Belgium? The first page would probably be the best. To make sure that every German searching user who does not match either de-at or de-ch gets that one, change that hreflang attribute to just de. Specifying just the language is in many cases a smart thing to do.

It’s good to know that when you create sets of links like this, the most specific one wins. The order in which the search engines sees the links doesn’t matter, it’ll always try to match from most specific to least specific.

6.1 Technical implementation basics

Regardless of which type of implementation you choose (more on that below), there are three basic rules.

1. Valid hreflang attributes

The hreflang attribute needs to contain a value that consists of the language, optionally combined with a region. The language attribute needs to be in ISO 639-1 format (a two letter code).

The region is optional and should be in ISO 3166-1 Alpha 2 format, more specifically, it should be an officially assigned element. This means you need to use this list for verification. This is where things often go wrong: using the wrong region code is a very common problem. Use the linked lists on Wikipedia to verify that you’re using the right region and language codes.

2. Return links

The second basic rule is about return links. Regardless of your type of implementation, each URL needs return links to every other URL, note that it should point at the canonical versions, more on that below. The more languages you have the more you might be tempted to limit those return links: don’t. If you have 80 languages, you’ll have hreflang links for 80 URLs. There’s no getting around that.

3. hreflang link to self

The third and final basic rule is about self-links. Just like those return links might feel weird at some point, the hreflang link to the current page feels weird for some developers. It’s required though and not having it will mean your implementation will not work.

6.2 Technical implementation choices

There are three ways to implement hreflang: using link elements in the, using HTTP headers or using an XML sitemap. Each has its uses, so we’ll discuss them and explain why you should choose any of these.

1. HTML hreflang link elements in your

The first method to implement hreflang we’ll discuss is HTML hreflang link elements. To implement hreflang using header link elements, you add code like this to thesection of every page:

As every variation needs to link to every other variation, these implementations can become quite big and lead to performance issues. If you have 20 languages, choosing HTML link elements would mean adding 20 link elements as shown above to every page. This means adding 1.5KB on every page load, that no user will ever use, but will have to download. On top of that, your CMS will have to do several database calls to generate all these links. This markup is purely meant for search engines. That’s why I would not recommend this for larger sites, as it adds far too much, unneeded, overhead.

2. hreflang HTTP headers

The second method of implementing hreflang is through HTTP headers. HTTP headers are the solution for all your PDFs and other non-HTML content you might want to optimize. Link elements work nicely for HTML documents, but not for other types of content as you can’t include them. That’s where HTTP headers come in. They should look like this:

Link: <http://es.example.com/document.pdf>;

rel=”alternate”; hreflang=”es”,

<http://en.example.com/document.pdf>;

rel=”alternate”; hreflang=”en”,

<http://de.example.com/document.pdf>;

rel=”alternate”; hreflang=”de”

The problem with having a lot of HTTP headers is similar to the problem with link elements in your: it adds a lot of overhead to every request.

3. An XML sitemap hreflang implementation

The third option to implement hreflang is using XML sitemap markup. It uses the xhtml:link attribute in XML sitemaps to add the annotation to every URL. It works very much in the same way as you would in a page’swith elements. If you thought link elements were verbose, the XML sitemap implementation is even worse. This is the markup needed for just one URL with two other languages:

http://www.example.com/uk/

You can see it has a self-referencing URL as the third URL, specifying the specific URL is meant for en-gb, and it specifies two other languages. Now, both other URLs would need to be in the sitemap too, looking like this:

http://www.example.com/

http://www.example.com/au/

As you can see, basically we’re only changing the URLs within the element, as everything else needs to be the same. This way, each URL has a self-referencing hreflang attribute, and return links to the appropriate other URLs.

XML sitemap markup like this is very verbose: a lot of output is needed to do this for a lot of URLs. The benefit of an XML sitemap implementation is simple: your normal users won’t be bothered with this markup. This has the benefit of not adding extra page weight and it doesn’t require a lot of database calls on page load to generate this markup.

Another benefit of adding hreflang through the XML sitemap is that it’s usually a lot easier to change an XML sitemap than to change all the pages on a site. No need to go through large approval processes and maybe you can even get direct access to the XML sitemap file.

7. Other technical aspects of an hreflang implementation

We’re going to assume that you’ve decided which type of technical implementation you’re going to choose. There are a couple of other technical specificities you should know about before you start implementing hreflang.

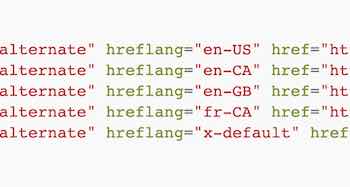

hreflang x-default

There is a special hreflang attribute value that’s called x-default. The x-default value specifies where a user should be sent if none of the languages you’ve specified in your other hreflang links match their browser settings. In a link element it looks like this:

When it was introduced, it was explained as being for “international landing pages”, ie pages where you redirect users based on their location. However, it can basically be described as the final “catch-all” of all the hreflang statements. If the users location and language didn’t match anything else, that’s where they will be sent.

In the German example we mentioned above, a user searching in English still wouldn’t have a “fitting” URL. That’s one of the cases where x-default comes into play. You’d add a fourth link to the markup, and end up with these 4:

de

de-at

de-ch

x-default

In this case, the x-default link would point to the same URL as the de one. We would not encourage you to remove the de link though, even though technically that would create exactly the same result. In the long run it’s usually better to have both as it specifies what language that de page is in and makes the code easier to read.

hreflang and rel=canonical

rel=”alternate” hreflang=”x”markup and rel=”canonical” can and should be used together. Every language should have a rel=”canonical” link pointing to itself. In the first example, this would look like this, assuming that we’re on the example.com homepage:

If we were on the en-gb page, not all that much would change other than the canonical:

Don’t make the mistake of setting the canonical on the en-gb page to http://example.com/, as this breaks the implementation. It’s very important that the hreflang links point to the canonical version of each URL. These systems should work hand in hand!

Useful tools when implementing hreflang

If you’ve come this far, you’ll probably be thinking “wow this is hard”, I know I thought that while learning about the topic. Luckily, there are quite a few tools available for people who dare to start implementing hreflang.

hreflang tag generator

Aleyda Solis, who has written quite a lot about this topic too, has created a very useful hreflang tag generator that helps you generate link elements. Even when you’re not choosing for a link element implementation, this can be useful to create some example code.

hreflang XML sitemap generator

The Media Flow have created an hreflang hreflang XML sitemap generator. You can feed it a CSV with URLs per language and it creates an XML sitemap. A very good first step when you decide to go this route.

The CSV file you feed this XML sitemap generator needs columns for every language. If you want to add an x-default URL to it as well, just create a column called x-default.

hreflang tag validator

Once you’ve added markup to your pages, you’ll want to validate that markup. If you choose to go the link element in theroute, you’re in luck, as there are a few validator tools out there. The best one we could find is flang, by DejanSEO.

Unfortunately, we haven’t found a validator for XML sitemaps yet.

Keeping hreflang alive: process

Once you’ve created a working hreflang setup, you need to set up processes. It’s probably also a good idea to regularly audit your implementation to make sure it’s still set up correctly.

Make sure that people in your company who deal with content on your site know about hreflang. This makes sure they won’t do things that break your implementation. Two things are very important:

When a page is deleted, check whether its counterparts are updated.

When a page is redirected, change the hreflang URLs on its counterparts.

If you do that and audit regularly, you shouldn’t run into many issues.

8. Conclusion

Setting up hreflang is a cumbersome process. It’s a tough standard with a lot of specific things you should know and deal with. This guide will be updated as new things are introduced around this specification and best practices evolve, so check back when you’re working on your implementation again!